La chasse de mammouths et d’autres grands proboscidiens est de mieux en mieux documentée au paléolithique, et pourrait avoir été pratiquée dès le paléolithique inférieur.

The hunting of mammoths and other large proboscideans is increasingly well documented in the Paleolithic era, and may have been practiced as early as the Lower Paleolithic.

Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., Earliest Evidence of Elephant Butchery at Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) Reveals the Evolutionary Impact of Early Human Megafaunal Exploitation, BioRxiv (preprint), 2025.

« At Olduvai Gorge, evidence for megafaunal butchery is scarce in the Oldowan of Bed I, but becomes more frequent and widespread after 1.8 Ma in Bed II, coinciding with the emergence of Acheulean technologies. Here, we present the earliest direct evidence of proboscidean butchery, including a newly documented elephant butchery site (EAK). This shift in behavior is accompanied by larger, more complex occupation sites, signaling a profound ecological and technological transformation. Rather than opportunistic scavenging, these findings suggest a strategic adaptation to megafaunal resources, with implications for early human subsistence and social organization. The ability to systematically exploit large prey represents a unique evolutionary trajectory, with no direct modern analogue, since modern foragers do so only episodically. »

Hauffe et al., Trait-mediated speciation and human-driven extinctions in proboscideans revealed by unsupervised Bayesian neural networks, Science Advances, 2024 [Texte]

« We estimated the proboscideans extinction rates to be most strongly affected by the overlap with humans, followed by more limited effects of geographic distribution and ecomorphology linked with tusk and mandible shapes. On the basis of partial dependent plots, the spatiotemporal overlap with early humans starting around 1.8 Ma was associated with a 5-fold increase in extinction rate, while the effect of modern Homo sapiens in the Late Pleistocene and Holocene was linked with a 17-fold increase. »

Gaudzinski-Windheuser et al., Widespread evidence for elephant exploitation by Last Interglacial Neanderthals on the North European plain, PNAS, 2023 [Texte]

« Based on Churchill’s (39) ethnographic data, one can infer that hunting of large elephants, no matter how dangerous (17), may have required little technological sophistication, with hunting strategies mostly aimed at limiting the mobility of prey, e.g., by digging pits or driving animals into mud traps that may have been present in abundance around the sites discussed here. However, hunting and subsequent processing did require cooperation and an investment of time. If meat and fat were prepared for storage, this would have added to the time investment.«

Gaudzinski-Windheuser et al., Hunting and processing of straight-tusked elephants 125.000 years ago: Implications for Neanderthal behavior, Science Advances, 2023 [Texte]

« Our archaeozoological study of the largest P. antiquus assemblage known, excavated from 125,000-year-old lake deposits in Germany, shows that hunting of elephants weighing up to 13 metric tons was part of the cultural repertoire of Last Interglacial Neanderthals there, over >2000 years, many dozens of generations. The intensity and nutritional yields of these well-documented butchering activities, combined with previously reported data from this Neumark-Nord site complex, suggest that Neanderthals were less mobile and operated within social units substantially larger than commonly envisaged.«

Sablin et al., 2023, The Epigravettian Site of Yudinovo, Russia: Mammoth Bone Structures as Ritualised Middens, Journal of Human Palaeoecology [Abstract]

« Our analyses indicate that hunting of both adult and young mammoths took place. »

Gary Haynes, Late Quaternary Proboscidean Sites in Africa and Eurasia with Possible or Probable Evidence for Hominin Involvement, Quaternary, 2022 [Texte]

« Lower Palaeolithic/Early Stone Age hominins created far fewer proboscidean site assemblages than hominins in later Palaeolithic phases, in spite of the time span being many times longer. Middle Palaeolithic/Middle Stone Age hominins created assemblages at eight times the earlier hominin rate. Upper Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age hominins created site assemblages at >90 times the rate of Lower Palaeolithic hominins. Palaeoloxodon spp. occur in nearly one third of the sites with an identified or probable proboscidean taxon and Mammuthus species are in nearly one half of the sites with identified or probable taxon. Other identified proboscidean genera, such as Elephas, Loxodonta, and Stegodon, occur in few sites. The sites show variability in the intensity of carcass utilization, the quantity of lithics bedded with bones, the extent of bone surface modifications, such as cut marks, the diversity of associated fauna, and mortality profiles.«

Gary Haynes, Sites in the Americas with Possible or Probable Evidence for the Butchering of Proboscideans, PaleoAmerica, 2022

« Suggestive traces of human use of carcasses such as associated stone tools or butchering marks vary from few or none in the oldest sites to relatively many in the latest (Clovis-era) sites. Evidence to distinguish scavenging from killing is not clear in most cases, but cut marks on bones in a few sites indicate that fully fleshed carcasses were butchered before carnivores stripped meat. Only one assemblage contains a bone with a possible weapon tip fragment embedded in it, a kind of find that is also rare in Eurasian mammoth sites. The oldest sites in the Americas are notably different from Old World assemblages, including those dating >1 Ma.«

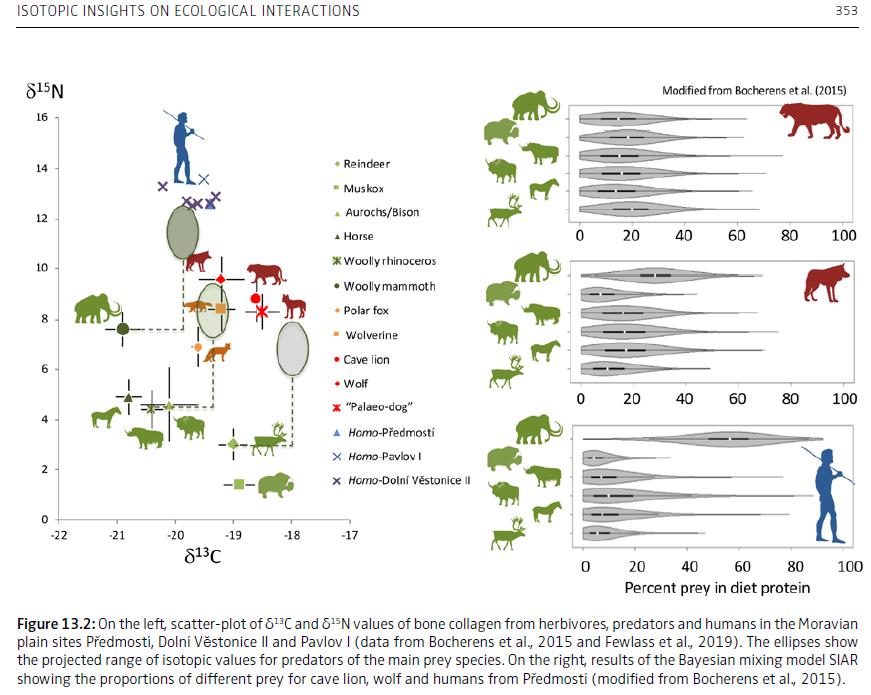

Hervé Bocherens, Dorothée G. Drucker, Isotopic insights on ecological interactions between humans and woolly mammoths during the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic in Europe, in Konidaris et al., Human-elephant interactions: from past to present, Tübingen University Press, 2021

« Carbon and nitrogen isotopic tracking with bone collagen has already yielded very important evidence for the high amount of mammoth meat consumption

by late Neanderthals in western Europe, and early modern humans in western, central and eastern Europe from around 45,000 to 30,000 years ago. […] «

Germonpré et al., Seasonality at Middle and Upper Palaeolithic sites based on the presence and wear of deciduous premolars from nursing mammoth calves USA, in Konidaris et al., Human-elephant interactions: from past to present, Tübingen University Press, 2021 [PDF]

« Indirect evidence, such as the accumulation of mammoth bones from multiple individuals with specific ontogenetic ages, occurs more frequently. Based on the eruption sequence and wear of deciduous premolars from mammoth calves, we examined whether a season of death could be deduced from the characteristics of the dentition. Our results suggest that the mammoth hunt was not restricted to the cold half of the year. »

Metin I. Eren et al., On the efficacy of Clovis fluted points for hunting proboscideans, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2021

« Clovis points are multi-functional tools, not specialized weapons for dispatching megafauna. Proboscidean hunting did not likely play a substantial role in the diet of Clovis groups.«

=> Commentaire : David Kilby et al., Evidence supports the efficacy of Clovis points for hunting proboscideans, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2022 [Texte]

« We find a number of weaknesses in their argument, including their estimations of mammoth anatomy, the validity of their experimental design, and their assumptions regarding Clovis hunting behavior. We evaluate their argument in light of ethnographic, experimental, and archaeological data and conclude that each of these datasets strongly supports the interpretation of Clovis points as weapons designed for use in hunting large animals, including proboscideans. »

=> Réponse au commentaire : Metin I. Eren et al., Not just for proboscidean hunting: On the efficacy and functions of Clovis fluted points, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2022

« Although multifunctional Clovis points were used to occasionally hunt mammoth, there is little reason to insist they were designed exclusively for that single task.«

Note personnelle : ça ressemble quand même à un gros rétropédalage de la part d’Eren et al.

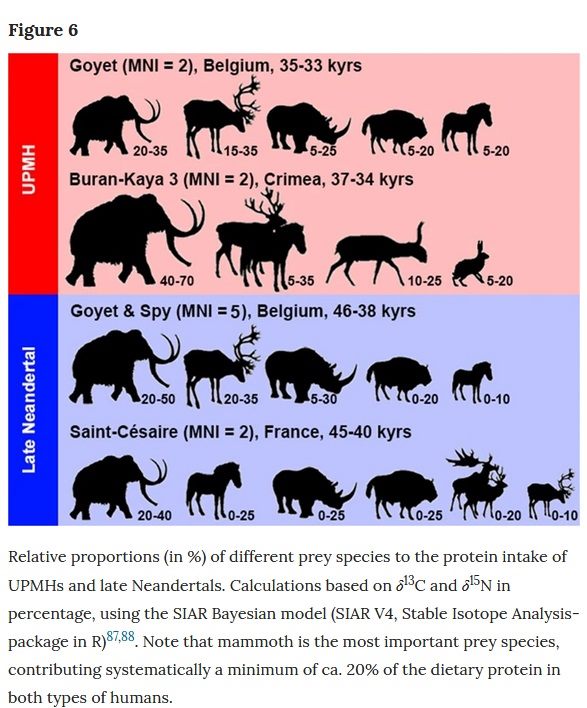

Wißing et al., Stable isotopes reveal patterns of diet and mobility in the last Neandertals and first modern humans in Europe, Scientific Reports, 2019 [Texte]

« For both UPMH individuals, the two most relevant prey species are the mammoth and the reindeer. Each species comprised roughly 25–30% of the meat protein source. The rhinoceros contributed ca. 15 to 20%, the bovines and horses around 10% of the dietary proteins. Cave bears played the least important role, with a maximum contribution of around 5% of the total protein intake. These results are similar to those of Neandertals, which indicates that both UPMHs and Neandertals had a similar prey choice with preference for mammoth and reindeer. […] The zooarchaeological records from Goyet and Spy fully support mammoth hunting episodes with a special preference for younger individuals and possibly their mothers. Interestingly, based on stable isotopes, the mammoth seems to contribute the major part of the dietary protein of humans in a time range between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago and across wide areas spanning from SW France to the Crimean Peninsula. »

Agam & Barkai, Elephant and Mammoth Hunting during the Paleolithic: A Review of the Relevant Archaeological, Ethnographic and Ethno-Historical Records, Quaternary, 2018 [Texte] [PDF]

« This study examines the archaeological evidence of proboscidean hunting during Paleolithic times, and provides a review of ethnographic and ethno-historical accounts, demonstrating a wide range of traditional elephant-hunting strategies. We also discuss the rituals accompanying elephant hunting among contemporary hunter-gatherers, further stressing the importance of elephants among hunter-gatherers. Based on the gathered data, we suggest that early humans possessed the necessary abilities to actively and regularly hunt proboscideans; and performed this unique and challenging task at will.

Wan & Zhang, Climate warming and humans played different roles in triggering Late Quaternary extinctions in east and west Eurasia, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2017 [Texte]

« Here, our analyses showed that temperature change had significant effects on mammoth (genus Mammuthus), rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae), horse (Equidae) and deer (Cervidae). Rapid global warming was the predominant factor driving the total extinction of mammoths and rhinos in frigid zones from the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. Humans showed significant, negative effects on extirpations of the four mammalian taxa, and were the predominant factor causing the extinction or major extirpations of rhinos and horses. Deer survived both rapid climate warming and extensive human impacts. »

Clapman & Capaldi, A simulation of anthropogenic Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) extinction, Historical Biology, 2017 [PDF]

« Previous research has been conducted on the overkill hypothesis for the Columbian mammoth using a continuous differential equations model. We improved on this work by developing a computationally more efficient and more realistic discrete stochastic model. Most model parameters were obtained directly from the literature; migration parameters were informed by the literature and calibrated for the model. Our results provide evidence in support of the overkill hypothesis. »

Piotr Wojtal et al., The earliest direct evidence of mammoth hunting in Central Europe – The Kraków Spadzista site (Poland), Quaternary science review, 2019 [Texte]

« The oldest unequivocal evidence of mammoth hunting in prehistoric Central Europe has been found in the Gravettian archaeological site Kraków Spadzista (Poland). The site contains thousands of lithic artifacts and the remains of >100 woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius), with radiocarbon dates clustering ∼25–24 ka uncal BP. A fragment of a flint shouldered point is embedded in a mammoth rib, and more than 50% of the site’s flint shouldered points and backed blades bear diagnostic traces of hafting and impact damage from use as spear tips. Additional support for mammoth killing is the mortality profile of 112 mammoths from the site: some age groups may have been depleted due to recurring heavy hunting by humans during periods of environmental stress. The evidence for intensive human hunting could portend a development thousands of years later, at the end of the Pleistocene, when climate-caused habitat changes were more extreme, and, in combination with opportunistic human hunting, may have led to woolly mammoth extinction.«

Drucker et al., Isotopic analyses suggest mammoth and plant in the diet of the oldest anatomically modern humans from far southeast Europe, Nature scientific reports, 2017 [Texte]

« The inferred human trophic position values point to terrestrial-based diet, meaning a significant contribution of mammoth meat, in addition to a clear intake of plant protein. »

Michael Dennis Cherney, Records of Growth and Weaning in Fossil Proboscidean Tusks as Tests of Pleistocene Extinction Mechanisms (thèse de doctorat), University of Michigan Library, 2016 [PDF]

« Tusk analyses for Ziegler Reservoir mastodons (Snowmass Village, CO) show no evidence that populations were struggling during the previous interglacial (Sangamonian) when climate was similar to current conditions. Poor nutrition is likely to result in later weaning age in mammals. However, in the interval of warming leading up to their extinction, Siberian woolly mammoths were apparently weaning earlier than they had been during the last glacial maximum. The shift to earlier weaning at the end of the Pleistocene refutes climate-related nutritional stress as a mechanism for their extinction. Population pressure from human hunting, which is expected to result in earlier weaning, is a more likely explanation for mammoth population declines.«

Pitulko et al., Early human presence in the Arctic: Evidence from 45,000-year-old mammoth remains, Science, 2016 [Abstract]

« Archaeological evidence for human dispersal through northern Eurasia before 40,000 years ago is rare. In west Siberia, the northernmost find of that age is located at 57°N. Elsewhere, the earliest presence of humans in the Arctic is commonly thought to be circa 35,000 to 30,000 years before the present. A mammoth kill site in the central Siberian Arctic, dated to 45,000 years before the present, expands the populated area to almost 72°N. The advancement of mammoth hunting probably allowed people to survive and spread widely across northernmost Arctic Siberia. »

Hagar Reshef & Ran Barkai, A taste of an elephant: The probable role of elephant meat in Paleolithic diet preferences, Quaternary International, 2015 [PDF]

« We suggest that early hominins might have had taste preferences and that elephant meat played a significant role in their diet, when available. Furthermore, the archaeological evidence coupled with ethnographic observations and the study of frozen mammoths suggest that juvenile elephants were specifically a delicacy and were hunted intentionally since their specific meat and fat composition seems to have had a better taste and a better nutritional value. »

Agam & Barkai, Not the brain alone: The nutritional potential of elephant heads in Paleolithic sites, Quaternary international, 2015 [PDF]

« The presence of elephants, and specifically of elephant head remains, is well demonstrated in many Paleolithic sites in Europe, Africa, and Asia. However, the possible mechanisms for the exploitation of this enormous body part are rarely discussed, and it is often suggested that elephants’ heads were exploited specifically for the extraction and consumption of the brain. In this paper, we discuss the nutritional potential that lies within elephants’ heads as implied by ethnographic and zoological literature, and present archaeological evidence from Paleolithic sites for the exploitation of proboscideans’ heads. The data show that the prevailing view should be re-evaluated, and that the nutritional potential within the elephant’s head extends far beyond the brain. We suggest that organs such as the temporal gland, the trunk, the tongue, the mandible and the skull itself were exploited routinely as an integral part of early humans’ diet. The nutritional potential of the elephant head provides a parsimonious explanation for the investment early humans put into transporting and exploiting this specific body part at open-air sites but particularly at cave sites, and serves as a significant beacon in understanding Paleolithic human behavior in relation to proboscidean remains. »

Bocherens et al., Reconstruction of the Gravettian food-web at Předmostí I using multi-isotopic tracking (13C, 15N, 34S) of bone collagen, Quaternary International, 2015 [PDF]

« Strong reliance on mammoth meat was found for the human of the site, similarly to previously analyzed individuals from other Gravettian sites in Moravia. Interestingly, the large canids interpreted as “Palaeolithic dogs” had a high proportion of reindeer/muskox in their diet, while consumption of mammoth would be expected from the availability of this prey especially in case of close interaction with humans. The peculiar isotopic composition of the Palaeolithic dogs of Předmostí I may indicate some control of their dietary intake by Gravettian people, who could have use them more for transportation than hunting purpose. »

Wojtal & Wilczynsky, Hunters of the giants: Woolly mammoth hunting during the Gravettian in Central Europe, Quaternary international, 2015

« Between 30,000 and 20,000 years ago, Gravettian hunter-gatherers spread across most of Europe. In Central Europe, large and important sites have been discovered, especially those in the Czech Republic at the base of the Pavlovské (Palava) Hills, and in southern Poland. The remains of different mammalian carnivores and herbivores accumulated in bone assemblages at these Gravettian sites. Mammoth bones and teeth are significant components in them. Mammoths certainly played a significant role in the lifetime of the Central European societies of Gravettian hunter-gatherers. These Pleistocene giants provided not only food, but also raw materials for tools and the production of ornaments. The presence of the remains of many mammoths shows that the Gravettian people were specialized in the hunting of these animals. »

Haynes & Klimowicz, Recent elephant-carcass utilization as a basis for interpreting mammoth exploitation, Quaternary International, 2015

« Both Pavlovian and Clovis people were close-range hunters who used spears and may or may not have had spear-throwers. The use of bow-and-arrow has also been proposed for Pavlovian, but not for Clovis. Both cultural complexes also probably used nets and snares to capture smaller animals. Lithic technology differed considerably – small blades in Pavlovian and bifaces in Clovis are the dominant forms. The larger Pavlovian settlements were preferentially situated in animal-migration bottlenecks, corridors connecting plains separated by mountains or highlands (Svoboda, 2007: 208). Herd animals that migrated through these corridors – reindeer, mammoths, horses – were hunted, and carnivores were also taken for food and furs, or for bones and teeth to use as raw materials. Clovis sites are not so preferentially located in such well defined physiographic settings in North America. The extent that animals other than mammoths were taken by Clovis hunters for food is not clear; a continent-wide faunal list from 31 Clovis-era sites includes ∼20 mammalian taxa, although not all of them may have been subsistence-related (Haynes and Hutson, 2013). »

Boschian & Saccà, In the elephant, everything is good: Carcass use and re-use at Castel di Guido (Italy), Quaternary international, 2015

(Dans un numéro fabuleux : The Origins of Recycling: A Paleolithic Perspective)

« These aspects indicate that the bones of large taxa, mostly elephant, were part of a complex subsistence system characterised by hunting and scavenging on one side, and an extremely fuzzy boundary among use, re-use and recycling on the other one. This system was based on the recycling – or transfunctionalisation – of the carcasses, which were exploited for food consumption (meat and possibly marrow), and later for raw material procurement over a long time of permanence and availability on the surface of the site. »

Pat Shipman, How do you kill 86 mammoths? Taphonomic investigations of mammoth megasites, Quaternary International, 2014 [PDF].

« The large number of individual mammoths and the scarcity of carnivore toothmarks and gnawing suggest a new ability to retain kill mammoths and control of carcasses. Age profiles of such mammoth-dominated sites with a large minimum number of individuals differ statistically at the p < 0.01 level from age profiles of Loxodonta africana populations that died of either attritional or catastrophic causes. However, age profiles from some mammoth sites exhibit a chain of linked resemblances with each other through time and space, suggesting the transmission of behavioral or technological innovation. I hypothesize that this innovation may have been facilitated by an early attempted domestication of dogs, as indicated by a group of genetically and morphologically distinct large canids which first appear in archaeological sites at about 32 ka B.P. »

Alexis Brugère, Not one but two mammoth hunting strategies in the Gravettian of the Pavlov Hills area, Quaternary international, 2014 (southern Moravia) [Extraits]

« two hunting strategies have been identified in the Pavlov Hills area: one affecting subadults and adults, and the second one affecting young and subadult individuals. Chronology and the physical condition of the mammoth population are not convincing arguments to explain such a difference. Human behaviour was involved, and we suggest economic goals related to mammoth resources were the reasons for such a hunting selection. »

Nikolskiy & Pitulko, Evidence from the Yana Palaeolithic site, Arctic Siberia, yields clues to the riddle of mammoth hunting, Journal of archeological science, 2013

« The data suggest that Palaeolithic Yana humans hunted mammoths sporadically, presumably when ivory was needed for making tools. Such non-intensive hunting practiced by humans over millennia would not be fatal to a sustainable mammoth population. »

Rabinovich et al., Elephants at the Middle Pleistocene Acheulian open-air site of Revadim Quarry, Israel, Quaternary international, 2012

« The unprecedented quantity of elephant remains at the site is accompanied by large and rich lithic assemblages. Of special interest are several elephant bones with cut marks, and the earliest appearance in the southern Levant of bones that seem to have been shaped to resemble tools. The site bears testimony to complex exploitation of proboscideans. »

Yravedra et al., Elephants and subsistence. Evidence of the human exploitation of extremely large mammal bones from the Middle Palaeolithic site of PRERESA (Madrid, Spain), Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012 [Texte]

Ben-Dor et al., Man the Fat Hunter: The Demise of Homo erectus and the Emergence of a New Hominin Lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant PLOS One, 2011 [Texte]

« The worldwide association of H. erectus with elephants is well documented and so is the preference of humans for fat as a source of energy. We show that rather than a matter of preference, H. erectus in the Levant was dependent on both elephants and fat for his survival. »

Waters et al., Pre-Clovis Mastodon Hunting 13,800 Years Ago at the Manis Site, Washington, Science, 2011 [Abstract]

« The Manis site, combined with evidence of mammoth hunting at sites in Wisconsin, provides evidence that people were hunting proboscideans at least two millennia before Clovis. »

Wei et al., New materials of the steppe mammoth, Mammuthustrogontherii, with discussion on the origin and evolutionary patterns of mammoths, Science China, Earth science, 2010 [PDF]

« The relationship between mammoths and humans deserves discussion. The coexistence of mammoth fossils and human remains or artifacts in many Paleolithic sites of Eurasia since the Pleistocene indicates that mammoths and humans inhabited the same biozone for a long time. For example, the coexistent interval of steppe mammoths and humans was at least 0.6 Ma in the Nihewan Basin of North China. The interval between the age of Majuangou site and Donggutuo site both including M. trogontherii fossils and artifacts was 1.7–1.1 Ma [16]. At the Majuangou site, one recovered rib of M. trogontherii with distinct chopping and scraping traces demonstrates mammoth-hunting by humans. There is synchronization between mammoth speciation and human evolution. The emergence of Australopithecus afarensis, Homo rudolfensis/Homo habilis, Homo erectus,and Homo heidelbergensis may correlate with the evolution of M. rumanus (3.5–3.0 Ma), M. meridionalis (2.6–2.5 Ma), M. trogontherii (1.8 Ma), and M. primigenius (0.8 Ma). On the other hand, the appearance of new species of mammoth, as many other terrestrial mega-mammals, closely follows palaeomagnetic reversal or global climatic events. »

Yravedra et al., Cut marks on the Middle Pleistocene elephant carcass of Áridos 2 (Madrid, Spain), Journal of Archaeological Sciences, 2010 [PDF]

« Cut marks have been found on the scapula and one rib of the elephant at Áridos 2, indicative of butchery and involving both defleshing and evisceration. This is suggestive of early access to the carcass by hominins. Haynes (2005) shows that viscerae disappear fast in the consumption of elephant carcasses by carnivores. This is also indicative of large carcass consumption during the Middle Pleistocene by hominins, not solely restricted to the Upper Pleistocen. »

Germonpré et al., Possible evidence of mammoth hunting during the Epigravettian at Yudinovo, Russian Plain, Journal of anthropological archeology, 2008 [PDF]

« The combination of the homogeneous weathering rate of the mammoth bones, the isolated state of most of the skeletal elements, the restricted spatial range of the carnivore gnawing traces, the breakage pattern of the skulls and long bones, the sex ratio, the small body size of the adult mammoths, the age profile (with an important frequency of prime-aged cows), and the large number of individuals, suggest that the bone complexes at Yudinovo were constructed from body parts and bones that were extracted from freshly killed mammoths and that mammoth hunting was practised at this site during the Epigravettian. »

Nogués-Bravo et al., Climate Change, Humans, and the Extinction of the Woolly Mammoth, PLOS Biology, 2008 [Texte]

« Results of the population models also show that the collapse of the climatic niche of the mammoth caused a significant drop in their population size, making woolly mammoths more vulnerable to the increasing hunting pressure from human populations. The coincidence of the disappearance of climatically suitable areas for woolly mammoths and the increase in anthropogenic impacts in the Holocene, the coup de grâce, likely set the place and time for the extinction of the woolly mammoth. »

Kathryn A. Hoppe, Late Pleistocene mammoth herd structure, migration patterns, and Clovis hunting strategies inferred from isotopic analyses of multiple death assemblages, Paleobiology, 2004 [PDF]

« High levels of variability in each of the isotope systems at Clovis sites suggest that all of the sites examined represent time-averaged accumulations of unrelated individuals, rather than the mass deaths of family groups. »

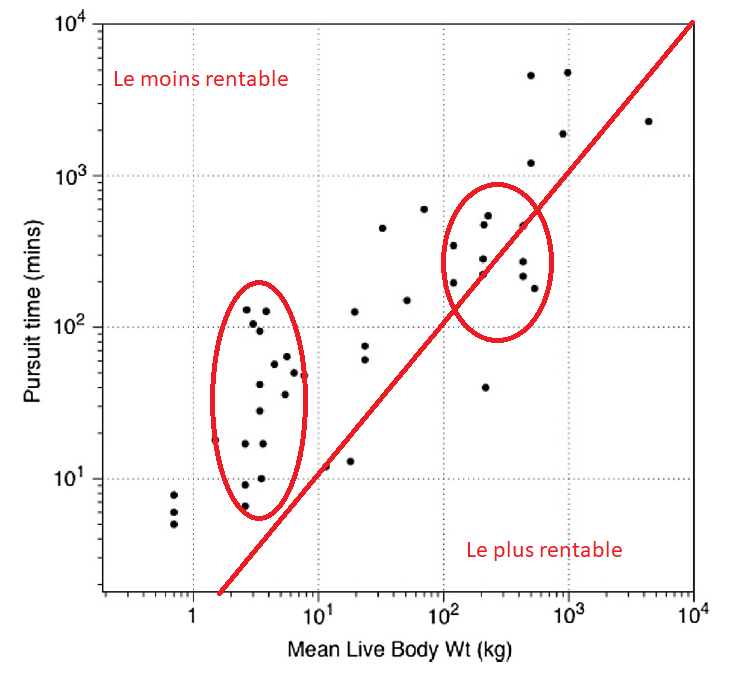

Grandes proies ou petites proies ?

Deconstructing Hunting Returns: Can We Reconstruct and Predict Payoffs from Pursuing Prey?

Morin et al. (Bliege Bird)

Journal of archeological method and theory, 2021

We find that body size is a poor predictor of on-encounter return rate, while prey characteristics and behavior, mode of procurement, and hunting technology are better predictors. Although prey body size correlates well with processing costs and edibility, relationships with pursuit time and energetic value per kilogram are relatively weak.

–

Brain expansion in early hominins predicts carnivore extinctions in East Africa

Faurby et al.

Ecology letters, 2020

hunting hominins are likely to behave in similar ways to other carnivores (Carbone et al. 1999) by focussing on relatively large prey (i.e. species of approximately the same body mass as themselves), selecting a few large prey items, rather than many small, and therefore competing more with large than with small carnivores.

–

The role of small prey in hunter–gatherer subsistence strategies from the Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene transition site in NE Iberia: the leporid accumulation from the Epipalaeolithic level of Balma del Gai site [Texte]

Rosado-Mendez et al.

Archeological and anthropological science, 2019

certain assumptions about energy return balances and the difficulty of a mass capture of individuals without a minimum of appropriate technology for exploitation to be economically profitable call into question that there is a specialized exploitation of this type of prey before the emergence and expansion of anatomically modern humans

–

Les paléoanthropologues lient la capacité de Néandertaliens à chasser le lapin à l’acquisition de « stratégies de chasse avancées » :

The exploitation of rabbits for food and pelts by last interglacial Neandertals [Texte]

Pelletier et al.

Quaternary science review, 2019

The capture of such a hight number of this small mammal potentially required sophisticated acquisition techniques formerly known only from Upper Palaeolithic contexts. […] In fact, despite the typically low return rates compared to ungulates (Speth and Spielmann, 1983; Ugan, 2005), the socio-economic potential of leporids is also reflected by the fact that both their bones and pelts can be exploited. The regular incorporation of small game in subsistence strategies during earlier periods, particularly the Middle Paleolithic, has been questioned by some researchers who argue that Neandertals, unlike modern humans, lacked the cognitive capacity and/or a sufficiently well-developed technology for regularly exploiting small game. […] The pattern of Middle Palaeolithic rabbit exploitation documented at Pié Lombard currently finds no equivalent in Europe for this period and provides indirect evidence for the development of advanced hunting strategies by Neandertals during MIS 5-4 as well as their advanced cognitive capacities.

–

When bigger is not better: The economics of hunting megafauna and its implications for Plio-Pleistocene hunter-gatherers [PDF]

Lupo & Schmitt

Journal of anthropological archeology, 2016

These data challenge the idea that prey body size can be used as a proxy for profitability and rank in zooarchaeological analyses. Prey profitability, especially for large-sized and costly taxa, is strongly influenced by prey characteristics relative to existing dispatch technology and the range of nonconsumptive benefits associated with hunting certain megafauna. Nonconsumptive rewards associated with these opportunities can only be gained by certain individuals and are not broadly available to everyone. We suggest that the idea of ‘big game’ specialization needs to be reframed in archaeology.

En rentabilité pure de la chasse, les proies de 100 à 500kg, en gros semblent les plus rentables. Si on ajoute les coûts de traitement (dépeçage, fumage, par exemple), la rentabilité s’équilibre. Néanmoins, la chasse devrait à mon sens être considérée comme l’acte le plus difficile, qui conditionne le reste. De plus, ce graphique est valable avec les armes récentes (arc…), mieux adaptées aux petites proies. Les chasseurs étudées récemment, de plus, tendent à chasser souvent individuellement, ce qui n’était pas forcément le cas au paléolithique. Une autre limitation est sans doute la disponibilité des proies, les grandes proies étant nettement plus rares aujourd’hui qu’au paléolithique, même si les espèces n’ont pas disparu. Un autre point à considérer est la présence d’éléments particulièrement intéressant présents sur certains animaux : fourrures ou peaux, ivoire, corne, taux de masse graisseuse, etc.

–

Il a été supposé que Néandertal aurait été moins capable de s’adapter à la chasse de petites proies, et, lorque la biomasse des grosses a diminué, cela lui aurait été fatal. On suppose désormais qu’il avait lui aussi la capacité technique de chasser des petites proies.

Rabbits and hominin survival in Iberia [Extraits]

Fa et al.

Journal of human evolution, 2013

We suggest that hunters that could shift focus to rabbits and other smaller residual fauna, once larger-bodied species decreased in numbers, would have been able to persist. From the evidence presented here, we postulate that Neanderthals may have been less capable of prey-shifting and hence use the high-biomass prey resource provided by the rabbit, to the extent AMH did.

–

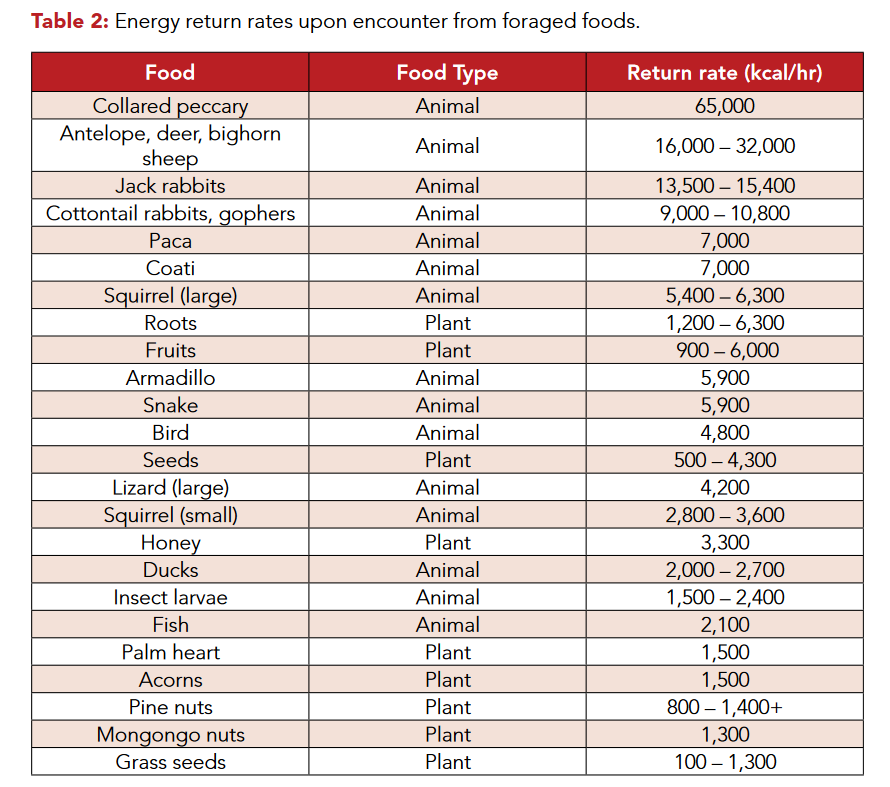

Paleolithic nutrition:what did our ancestors eat?

Brand-Miller et al, 2009

Table 2 shows the energy return rates for a variety of plant and animal foods that were known components of hunter-gatherer diets. Clearly, animal foods yield the highest energy return rates, and larger animals generally produce greater energy returns than smaller animals. Although the potential food mass would be similar between a single deer weighing 45 kg and 1,600 mice weighing 30 g each, foraging humans would have to expend significantly more energy capturing the 1,600 mice than a single deer. Hence, the killing of larger animals increases the energy capture/energy expenditure ratio not only because it reduces energy expenditure, but because it in-creases the total energy captured.

Divers

Recent elephant-carcass utilization as a basis for interpreting mammoth exploitation

Haynes, 2015

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040618213009749